Shriya Gupta

The Paradox of Growth Without Welfare

“Gross Domestic Product… measures everything except that which makes life worthwhile.”

~Robert F. Kennedy

India has emerged as one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, consistently posting high GDP growth rates over the past three decades. However, this growth has often coexisted with stagnant or worsening indicators of human development, environmental sustainability, and social equity. Air and water pollution, income inequality, poor access to health and education, and displacement due to industrial expansion reveal a troubling paradox: India’s booming GDP masks widespread welfare failures. In order to guarantee that economic growth is in line with long-term environmental well-being, India must embrace Green GDP and natural capital accounting immediately.

GDP Growth vs. Welfare Decline

Originally conceptualized by Simon Kuznets in the 1930s, ignores the fundamental role that human, social, and natural assets play in maintaining economies. Although it measures economic production, it is not a good representation of the state of society.

GDP Growth:

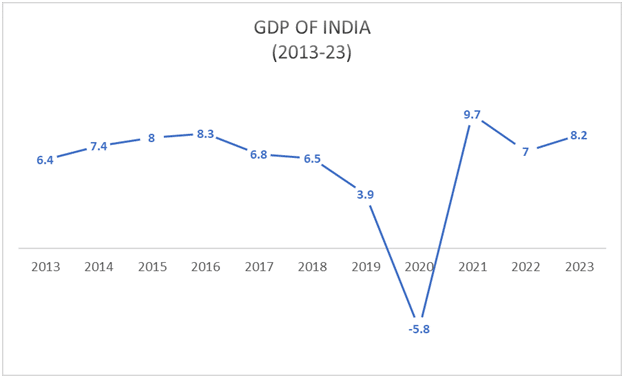

While India’s GDP increased from 6.4% in 2013 to 8.2% in 2023, social and environmental indicators highlighted ongoing concerns.

Welfare failures:

- Rising Inequality: Despite rising GDP, income inequality in India has widened. The Gini coefficient rose to ~0.51 in 2013 and ~0.52 by 2020. By 2022, the wealthiest 1% of Indians controlled more than 40% of national wealth, reflecting a lopsided distribution of benefits and a growing disparity between affluent and poor.

- Poverty & Multidimensional Deprivation: While income poverty has decreased, more than 11% of India’s population remains in multidimensional poverty, with limited access to nutrition, education, and sanitation. Between 2013 and 2023, approximately 248 million individuals were lifted out of poverty, although deprivation remains high in marginalized communities. GDP growth alone does not overcome these problems.

- Lagging Health and Social Spending: India spends just around 2.1% of GDP on public healthcare and 3% on education, well below global averages. Despite economic growth, investment in essential public services remains inadequate. Millions lack access to reliable healthcare, safe drinking water, and quality schooling, undermining the overall impact of GDP growth on welfare.

- Environmental Costs: GDP growth overlooks environmental costs. India ranked 3rd worst globally in air quality in 2023, with pollution-linked deaths exceeding one million annually. Urban development often displaces forests and biodiversity. Green GDP, which adjusts for ecological harm, remains largely unadopted despite its relevance to sustainable welfare measurement.

Thus, it offers a narrow and often misleading snapshot of national progress. Without broader metrics, overreliance on GDP risks promoting short-term gains at the cost of long-term societal and environmental stability.

Green GDP

It aims to provide a more accurate picture of a nation’s true economic performance by adjusting traditional GDP figures to account for environmental damage and the consumption of natural capital. It highlights the hidden costs of economic activities that harm ecosystems and deplete resources, offering a more balanced view of progress. It encourages policymakers to internalize environmental externalities, invest in renewable energy, and promote welfare and sustainable practices. Although the methodology is still evolving, researchers like Pokharel and Bhandari (2017) emphasize the need for standardized valuation systems to accurately assess environmental costs. While still in its early stages, Green GDP represents a significant step toward aligning economic growth with ecological and social well-being.

Challenges

- Methodological Challenge: Assigning monetary value to environmental services is inherently difficult. Ecosystems are complex, and many benefits—such as cultural heritage, biodiversity, and clean air—are intangible. Moreover, different valuation methods (e.g., contingent valuation, hedonic pricing) yield inconsistent results, complicating policy application.

- Institutional Challenge: India’s institutions frequently oppose adopting new metrics. Bureaucratic inertia means that systems adhere to established GDP-centric practices. Furthermore, divided governance and political control by elite interests block reform initiatives. Even when environmental accounting obtains momentum, implementation fails owing to a lack of political will and accountability.

- Political Economy Challenge: Industries and political elites benefit from existing growth-focused metrics. After 1991, corporate influence became more assertive in steering policy agendas. Environmental accounting threatens profit margins and regulatory privilege. Consequently, initiatives like Green GDP face pushback rooted in the entrenched state–business nexus, electoral financing, and powerful corporate lobbies.

Alternative Indices

- Human Development Index (HDI): HDI is a composite index developed by the UNDP that measures average achievement in three key dimensions: health (life expectancy), education, and standard of living (GNI per capita). It offers a broader perspective on development than GDP but does not account for inequality or environmental sustainability.

- Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI): MPI measures poverty not just by income but through deprivations in health, education, and living standards. It captures the intensity and breadth of poverty within populations, offering a more nuanced understanding than income-based poverty lines. However, it depends heavily on large-scale household data and may not reflect real-time conditions.

- Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI): GPI modifies GDP by including positive contributions (like volunteer work) and subtracting negative factors (like pollution, crime, and income inequality). It aims to reflect actual societal well-being and sustainable economic welfare. GPI is more aligned with long-term development goals but is difficult to standardize and sensitive to assumptions.

- Social Progress Index (SPI): This metric assesses a country’s social progress at both national and subnational levels. The index evaluates states and districts based on 12 components covering three key characteristics of socioeconomic progress: Basic Human Needs, Foundations for Wellbeing and Opportunity. The index utilizes a comprehensive framework with 89 indicators at the state level and 49 at the district level.

Policy Directions

- Integrate Green GDP & Alternative Indicators: India’s MoSPI has started environmental accounting under SEEA; however, implementation is still restricted. Incorporating Green GDP and measures such as HDI and SPI into national dashboards, which are commonly used in policymaking, could promote sustainable and equitable growth.

- Strengthen Public Investment in Welfare: Public health expenditure has nearly tripled, rising from ₹1,042 per capita in 2013–14 to ₹3,169 in 2021–22, with government spending’s health share doubling from 28.6% to 48%. CSR spending on health, education, and the environment reached ₹26,278 cr in 2021–22, channeling funds into critical sectors.

- Reform Fiscal & Industrial Policy: Despite environmental levies, Delhi-NCR spent only 31% of green fund collections over the last decade—a mere 1% utilization of the environmental cess—revealing weak policy enforcement. Fiscal reforms, such as pollution taxes and green subsidies, can align industrial incentives with sustainability.

Conclusion

India’s economic growth story masks a deeper welfare deficit. Despite rising GDP, vast sections of the population continue to face poverty, inequality, and environmental degradation. This paradox highlights the inadequacy of GDP as a standalone measure of development. Green GDP offers a more accurate alternative by accounting for ecological costs, while indicators like HDI, MPI, and SPI provide multidimensional views of progress. However, adopting these measures requires strong political will, institutional reform, and a shift in policy priorities. Economic success must be redefined not just by how much we produce, but by how equitably and sustainably we grow. A development model centered on equity, environment, and human well-being is essential if India is to ensure that its economic progress truly benefits all citizens and preserves resources for future generations.

Referrals

https://naos-be.zcu.cz/server/api/core/bitstreams/f948ef47-374d-41b6-b142-82fe7dc0c82d/content

https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index

What is an MPI?

https://www.pmfias.com/healthcare-expenditure-in-india

https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/eco-valuation-regulation-guide#implementation-challenges

en.wikipedia.org+3thehindu.com+3health.economictimes.indiatimes.com.