By – Simran Kaur

Signed on August 15, 1985, between the Government of India and the leaders of the Assam Movement, the Assam Accord is a significant document meant to address long-standing concerns over illegal immigration and its impact on Assam’s socio-political milieu. Clause 6 of the Accord stipulates the provision of constitutional, legislative, and administrative safeguards for the preservation of the “cultural, social, linguistic identity, and heritage” of the Assamese people. As important as it is, its implementation remains inconsistent and just within the narrow context. In fact, a few new developments in 2024 signal a revival of the promise to fulfill this commitment. The paper analyzes the background, objectives, challenges, and the latest development regarding the implementation of Clause 6, thus offering a holistic view of its effects on the Assamese people.

The Assam Movement (1979-1985) was triggered by fears that illegal immigration from Bangladesh would erode the cultural and demographic domains. The growing influx, particularly since the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, heightened fears of the Assamese communities regarding the possible loss of political power, cultural identity, and rights to resources. The prolonged crisis created social unrest and gave rise to massive protests spearheaded by the All-Axam Students’ Union (AASU) along with some other regional organisations. Some of these protests turned violent and sought stern action for instilling indigenous rights.

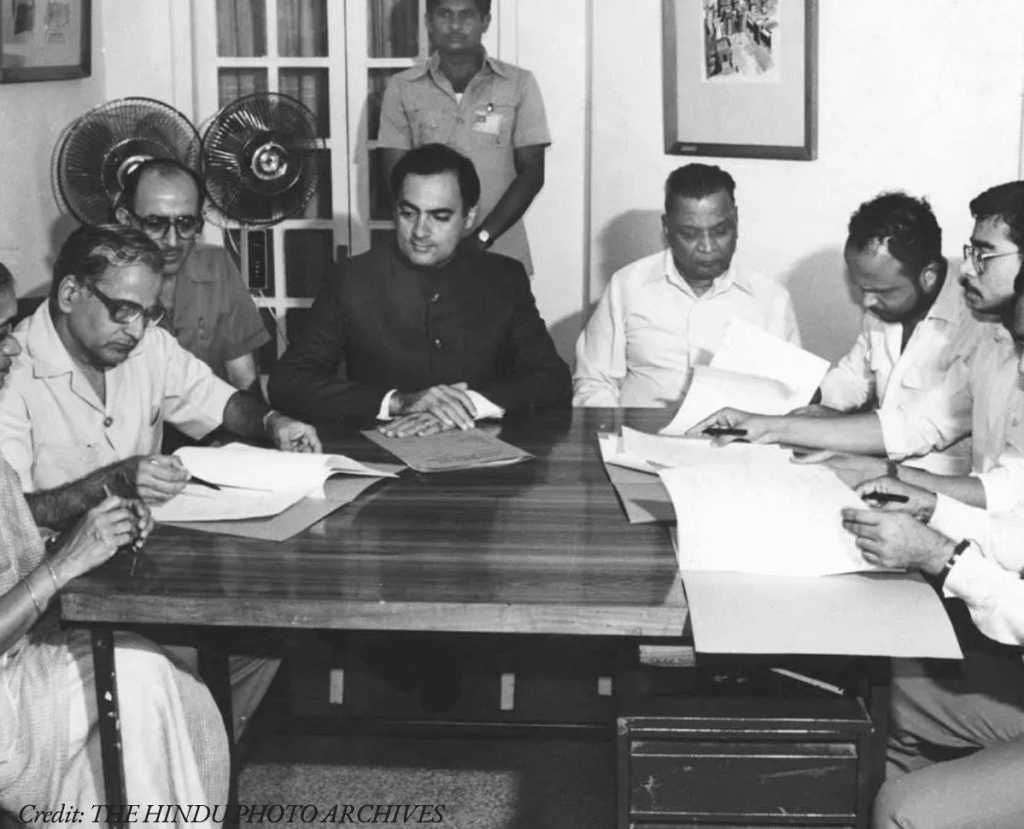

The Assam Accord was finally signed on August 15, 1985, by leaders of the movement and the Government of India promising a solution to these problems. The particularly prominent Clause 6 of the Accord sought to protect the socio-cultural and linguistic identity of the indigenous Assamese communities through a combination of constitutional, legislative, and administrative measures. The ambitious scheme virtually guarantees ambitious goals, but implementation of the clause is stymied by the absence of a clear direction, a lack of political will, and a lack of clarity in defining “Assamese people.” These unresolved issues have led to an impasse extending for decades, and the Accord promises have not fully seen daylight.

Clause six envisages the safeguarding and promotion of Assamese identity in areas of vital importance to the same. At the center are the safeguarding of Assamese language, literature, andculture. This will deal not only with the setting up of Government Financed Cultural Institutions but also grants to support local art forms and education for the Assameselanguage, thus ensuring the rich heritage which Assamese provides by passing it on from generation to generation.

As far as Clause VI is concerned, social safeguards are a very important element. Since it envisions providing indigenous Assamese with an equalised approach to essential services, such as health care and education, and within welfare projects, it is deemed a nature to cervantise impassable social and economic skewedness.The political representation is another striking mechanism of this provision. It proposes reserved seats in legislative bodies, local councils, and government institutions so that political equality and the voice of the indigenous Assamese people in decision-making are asserted. This is part of their empowerment, which must aid their long-term survival and preservation of identity, interests, and culture.

Clause 6 also aims to protect traditional lands and resources. Demographic displacement will be avoided and full ownership of ancestral lands will remain within the hands of natives through the reservation of land ownership to indigenous Assamese.

Ultimately, the clause puts forth economic opportunities in preferential treatment of Assamese people in public sector jobs, entrepreneurship, and skill development programs. These things could help the community develop themselves economically and strengthen their resilience toward external pressures.

The implementation of Clause 6 draws several hurdles, crispy out with dares confounds here from the rug to mind.Apparently, this absence of a clear definition of “Assamese” happens to rattle several feathers; indigenous tribes, the Bengali-speaking population, and religious minorities included. To identify the people who should be graded in this preferential treatment, no one, because, without a clear legal definition, such a program is so very tough to be implemented, even targeted enough to avoid community tensions.

Another major obstacle stemming from Assam is the ethnic and demographic diversity. The state of Assam shelters varied tribes, such as the Bodos, Rabhas, Karbis, Koch-Rajbongshis, all with distinct cultural and linguistic identities. Prioritizing protection for “Assamese” unfortunately casts these communities in an exclusionary glare, invariably aggravating inter-marriage. It remains a penance trying to juggle the various community interests in the implementation of the clause.

Political and bureaucratic bottlenecks seem to toggle progress with every passing day. Government after government shrink back from aggressive action, tipped mainly yet not solely on the fear of losing elections and possibly inviting social unrest. The inertia, terribly bad bureaucracy, and no planned agreement of deployments have caused a sharp rise in unwanted delays, so that their wished status proposals have remained mostly unfinished.

Finally, added to this are the legal and constitutional impediments. Reservations in jobs or buying land, for instance, might need amendments to the Indian Constitution; a long and laborious process undertaken on a triply rejected idea. One such hurdle, one such legal match, must fall within the bounds of the general Indian laws.

In addition, certain provisions of Clause 6, such as the restriction of land rights or employment opportunities to specific communities, may clash with the constitutional guarantees of equal rights and opportunities for all Indian citizens. Conflicts can be litigated in courts, further delaying implementation.

This requires a synergistic effort where the aspirations of Assamese people may be matched against the goals of inclusion and constitutional equilibrium, wherein the objectives embodied by Clause 6 shall not go at the expense of inciting further social and political disturbance.

The Justice (Retd) Biplab Sarma Committee report has provided a full set of recommendations aimed at ensuring the rights and identity of the Assamese people under Clause 6. Assam Chief Minister said, “The state government already has a roadmap for putting these recommendations into action – which have been categorized by jurisdictional authority and procedural requirements”.

Out of 67 recommendations, 40 lie completely within the sphere of the state government. These include the critical area of promoting cultural heritage and preservation of the Assamese language, and introduction of job reservations in public sector jobs under the direct control of the state. All these measures are under implementation, and the state government is giving priority to those policies that can be independently implemented at the state level. Initiatives include the establishment of institutions to preserve Assamese culture and heritage, providing financial support for traditional art forms, and state jobs for indigenous Assamese youth.

However, 12 of the recommendations need approval from the Government of India. These include constitutional amendments that limit land ownership rights and provide for reserved seats in legislative bodies for Assamese people, provisions that call for compliance with national laws. The state government has assured to interact with the central government to seek those approvals, realizing their importance for the proper implementation of Clause 6’s safeguards.

To ensure more transparency and facilitate coordination, the Assam government has assured that it would present an elaborate implementation schedule to the AASU by October 25, 2024. It would encompass time lines, strategies, and steps to implement the recommendations at the state as well as the central levels. The government is working to prove accountable and create confidence among stakeholders through participation by civil society and ethnic bodies.

The roadmap also considers ethnic diversity in Assam, in particular in Sixth Schedule districts such as Dima Hasao and Karbi Anglong. Special provisions and continued dialogues with tribal councils in such areas will help strike the right balance between local demands and the larger objectives of Clause 6.

This is a balanced approach that combines urgency with inclusiveness. It tackles issues at the state and central levels as well, promoting the collaboration of stakeholders so that the implementation of recommendations could be smooth and efficient to ensure the realization of aspirations of Assamese people while sustaining constitutional and social harmony.

This would form an important moment of fulfilling some of the long-standing demands while protecting the distinctive Assamese culture. Clause 6 of the Assam Accord is not a piece of legislation but rather the outcome of the long and consistent aspirations of the Assamese people. While much has been accomplished in 2024, with the Justice (Retd) Biplab Sarma Committee getting crucial recommendations approved, there are many more challenges ahead. Sustained and inclusive efforts will be required to meet the objectives of the clause as it cuts through complex legal, political, and social complexities.

A primary challenge lies in striking a balance among the diverse interests of Assam’s multifaceted communities. With its tapestry rich in ethnic groups, linguistic identities, and tribal populations, the state needs sensitive policymaking so that no one group is offended. Special provisions to areas governed under the Sixth Schedule, like Dima Hasao and Karbi Anglong, demonstrate the significance of dealing with regional and tribal concerns together with the overarching goals of Clause 6.

Legal and constitutional hurdles also demand attention, especially with provisions such as land ownership restrictions and job reservations, which require changes to accommodate national laws. Equally important is defining the term “Assamese people” in a manner that is both inclusive and specific, ensuring that targeted implementation does not create inter-community conflicts.

Success for Clause 6 requires creating trust and harmonious relationships between the central and the state authorities, involving groups such as AASU as part of civil society, through transparent governance practice that regularly consults to have the public confidence well-protected.

The Assam government would be able to fulfill the promises of Clause 6 through a holistic approach emphasizing equal safeguards, cultural preservation, and economic empowerment. This is an historic opportunity not only to address historical grievances but also lay the foundation for a harmonious, inclusive, and prosperous Assam. It will be possible only if sustained commitment and transparent implementation take place to deliver justice to the indigenous Assamese people and preserve their identity for future generations.

REFERENCE –

- https://www.business-standard.com/india-news/will-implement-52-recommendations-on-clause-6-of-assam-accord-says-cm-124090700635_1.html

- https://assamaccord.assam.gov.in/information-services/assam-accord-and-its-clauses

- https://www.business-standard.com/india-news/what-is-clause-6-of-assam-accord-himanta-govt-to-implement-its-provisions-124092700359_1.html

- https://vajiramandravi.com/upsc-daily-current-affairs/mains-articles/implementation-of-clause-6-of-assam-accord/